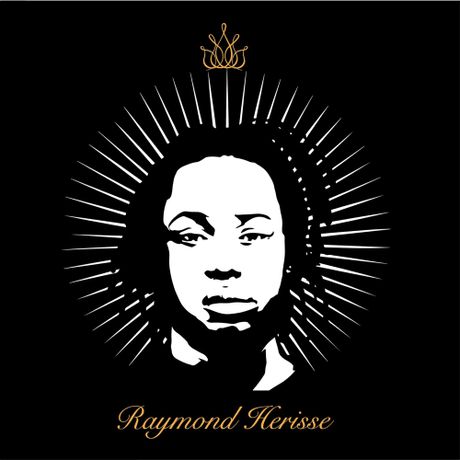

A federal appeals court in Florida has upheld a previous court’s ruling that the removal of a mural depicting 22-year-old Haitian American Raymond Herisse, who was shot dead by police during Miami Beach’s 2011 Urban Beach Weekend festival, was not an act of censorship.Last week, a three-judge panel upheld the previous decision, made last year, in which the US District Judge Marcia G. Cooke concluded that because the artwork had been commissioned (both its creation and curation) by the city of Miami Beach, its subsequent removal from the municipal programme constituted an act of “government speech” and could therefore not be considered within First Amendment rights.”The court’s disappointing decision does not mean that the censorship by the Miami Beach police was justified. The [American Civil Liberties Union] of Florida will continue to fight against such government-sanctioned discrimination,” says Daniel Tilley, legal director of the ACLU, which originally filed the lawsuit on behalf of the artists and curators, in 2020.The artists and curators behind the 4ft by 4ft work—Jared McGriff, Octavia Yearwood, Rodney Jackson and Naoimy Guerrero—claimed that their free speech was challenged when the work, Memorial to Raymond Herisse (2019) by Jackson, installed at the I See You, Too project, set within the broader project ReFrame Miami Beach programme, was removed soon after installation. A sign replacing the work confirmed that it had been removed “at the request of Miami Beach Police”.Court proceedings throughout the process have identified the broader context to the dispute, specifically a long history of racial tensions in Miami Beach. The initial lawsuit named the former Miami Beach city manager, Jimmy Morales, and the Miami Beach mayor, Dan Gelber, but both names were later removed from legal proceedings.The latest papers outline the court’s opinion, which arrived at the conclusion that “there is no genuine dispute of material fact that the city was speaking when it selected some artwork, but not others, to display at ReFrame”. It went further to argue, citing precedents, that just as “governments are not obliged under the First and Fourteenth Amendments to permit the presence of a rebellious army’s battle flag in the pro-veterans parades that they fund and organise” they are likewise “not obliged to display any particular artwork in the art exhibitions that they fund, organise and promote”. Nevertheless, the panel did add that this “does not absolve Miami Beach from criticism from its decision”.Legal representatives from the City of Miami have not yet responded to The Art Newspaper’s request for comment. Meanwhile, Alan Levine, co-counsel with the ACLU of Florida says: “The city’s behaviour in this case does not bode well for the city’s willingness to reckon honestly with its history of racism nor for its willingness to tolerate artistic expression with which it disagrees.”